The findings require more research, but may prove to be important in the treatment of addiction and anxiety disorders, said Elements CEO Dr. David Sack. Might dropping acid drop your anxiety? Could you better cope with health threats by taking a guided LSD trip with your therapist? The unlikely answer is maybe. LSD’s image is psychedelic party drug, glorified in the cryptic Beatles song, “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” According to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, possessing just one gram of LSD would get you a mandatory five years in prison. But the first research in 40 years testing lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) has found that it markedly reduced anxiety in patients facing life-threatening diseases. The results of the study of LSD use as a supplement to psychotherapy were published this month online in the peer-reviewed Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. “The double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study in 12 subjects found statistically significant reductions in anxiety associated with advanced stage illness following two LSD-assisted psychotherapy sessions,” announced the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, which sponsored the study. “The results also indicate that LSD-assisted psychotherapy can be safely administered in these subjects, and justify further research.” The lead doctor — who has taken LSD himself during therapy — said he found the results encouraging for what the LSD did for patients as well as what it did not do.

No Adverse Effects

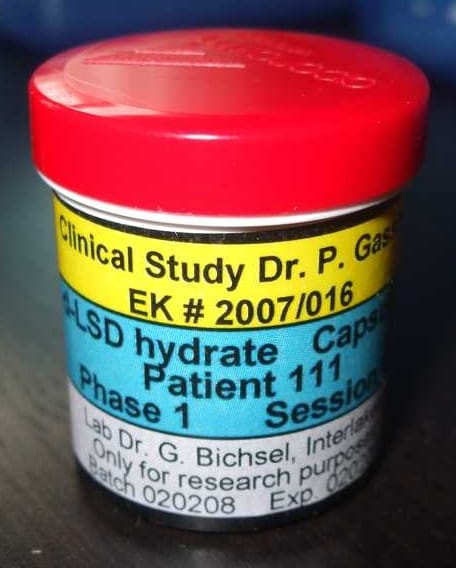

“The study was a success in the sense that we did not have any noteworthy adverse effects,” principal investigator Peter Gasser, a psychiatrist practicing in Solothurn, Switzerland, said in a news release. “All participants reported a personal benefit from the treatment, and the effects were stable over time.” One of the participants in the clinical trial described an emotional departure from the clench of worry and panic over his mortality — an altered state and a classic hallucinogenic trip. “My LSD experience brought back some lost emotions and ability to trust, lots of psychological insights, and a timeless moment when the universe didn’t seem like a trap, but like a revelation of utter beauty,” Peter, an Austrian research subject, said in the LSD research announcement. Decades of LSD use to treat alcoholism and other conditions were abandoned in the late 1950s and 1960s, when the hallucinogenic burst into popularity. LSD was typecast as a recreational drug trip for the counter-culture — note current media stories of hippies in bare clothing. The U.S. Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, signed by President Richard Nixon, which classified LSD as Type 1 — reserved for the most dangerous substances and deemed a drug with no medical value. That stigma, researchers note, left the impression that LSD was too risky to employ in humans, despite extensive use decades earlier treating thousands of patients with depression, alcoholism, anxiety — even existential angst.

LSD ‘Not Uniquely Dangerous’

“I think we have to say these drugs are not uniquely dangerous,” said Dr. David Sack, a national expert on addiction and treatment who is CEO of Promises Behavioral Health. “The way we have to look at it, is that just because some people abuse painkillers does not mean that we stop treating surgical patients or car crash victims with painkillers. Just as there are legitimate uses for pain medications, there may be legitimate uses for this type of medicine. We basically outlawed a whole class of medications because of the street abuse by some in the 1960s.” In the same vein this month, Scientific American editors, with noted exasperation, called for LSD’s return to wider clinical trials: “The decades-long research hiatus has taken its toll. Psychologists would like to know whether MDMA [also known as Ecstasy] can help with intractable post-traumatic stress disorder, whether LSD or psilocybin [also known as ‘magic mushrooms’] can provide relief for cluster headaches or obsessive-compulsive disorder, and whether the particular docking receptors on brain cells that many psychedelics latch onto are critical sites for regulating conscious states that go awry in schizophrenia and depression. “In many states, doctors can now recommend medical marijuana, but researchers cannot study its effects. The uneasy status quo leaves unanswered the question of whether the drug might help treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, nausea, sleep apnea, multiple sclerosis and a host of other conditions.” The findings require further research but may prove to be important for treatment of addiction and anxiety disorders, Dr. Sack said. Proponents of exploring the applications of LSD note that while research before 1950 lacked today’s clinical trial protocols, the hallucinogenic had been used with thousands of patients in psychiatry. It was another Swiss man who discovered the psychoactive drug in 1938. LSD was first “synthesized from a fungus that grows on rye and other grains,” according to the University of Washington. Chemist Albert Hofmann was 32 and working for a pharmaceutical firm. “He was hoping that this new drug could be used to stimulate circulation and respiration. However, the tests he conducted were all failures and he forgot about LSD for five years. In 1943, Hofmann accidentally ingested (or somehow absorbed) a bit of LSD and experienced some of the psychedelic effects of this chemical: dizziness, visual distortions and restlessness. A few days later he prepared 0.25 mg of LSD in water and drank it. He again experienced the mood and thought-altering effects of LSD.” According to Dr. Sack, “Many of the rewarding and mood elevating effects of alcohol appear to be mediated by the serotonin system, the same system that is targeted by LSD. A number of serotonin-elevating medicines that are in use as antidepressants have been studied for alcohol dependency without success. LSD’s effect on serotonin receptors is uniquely different from these other medicines and merits additional investigation.” Hofmann championed LSD’s use in science and medicine. He witnessed — to his horror — the acid-tripping 1960s that brought on criminalizing LSD. Seventy years after he discovered LSD, Gasser’s early pursuit of testing LSD on patients began in 2008. Hoffman died that year at age 102. After taking LSD himself during psychotherapy, Gasser was intrigued with its potential to help people with mental health challenges. For years, finding research funding and willing subjects proved elusive. Dr. Sack noted that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration likely approved the clinical trials only because the patients were stricken with life-threatening diseases such as cancer.

Characteristics of Hallucinogens

Odorless, colorless and tasteless, LSD is a chemical classified as a hallucinogen. The user typically experiences shifts in perception, thinking and mood. A user may experience paranoia, panic, confusion, anxiety, hallucinations, a dream-like state and see vivid colors — hence the psychedelic label. According to the University of Washington, LSD may cause a wave of emotions, not necessarily positive. Ten other characteristics have been noted:

- Powerful enough that ingesting a grain the size of salt (.010) can cause behavioral changes.

- Euphoria

- Heightened sense of awareness

- Feeling unreal or that the things around you are not real

- Insomnia during the “trip”

- Distortion of the senses and of time and space

- “Flashback” reactions — effects even after the user hasn’t taken LSD for months or years

- Increase in heart rate and blood pressure

- Chills

- Muscle weakness

Though it is still not fully understood what creates all of the effects of LSD, many of its actions have been attributed to its effects on serotonin, a neurochemical that plays important roles in the regulation of mood, appetite, energy and sleep as well as stress responses, Dr. Sack said. LSD both inhibits the release of serotonin by neurons in the brain stem via the 5HT1 receptor and mimics serotonin’s effects at other neurons by binding to the 5HT2 receptor. The effects of LSD are believed to be caused by a combination of these effects. Some of the rewarding effects of alcohol are mediated by yet another serotonin receptor, the 5HT1b and 5HT3 receptors. “Abnormalities in the regulation of serotonin are thought to mediate the high rates of suicide seen in alcoholics as well as patients with depression,” Dr. Sack said. “An effective treatment that could re-regulate serotonin neurons could decrease relapse rates and mortality rates in alcoholics undergoing treatment.” More than 30 million people in the U.S. have used LSD, psilocybin, or mescaline. The psychedelics do not cause brain damage and are considered by medical professionals to be non-addictive. Scientific American editors back in September, 2009, remarked on the early struggles by Gasser to launch clinical trials. “A number of the hundreds of studies conducted on lysergic acid diethylamide-25 from the 1940s into the 1970s (many of poor quality by contemporary standards) delved into the personal insights the drug supplied that enabled patients to reconcile themselves with their own mortality. In recent years some researchers have studied psilocybin (the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms”) and MDMA (Ecstasy), among others, as possible treatments for this “existential anxiety,” but not LSD.” The time for that change, they said, is long overdue. From Scientific American, which in February 2014 called for a lifting of government restrictions and stigma on LSD’s use in research for potential medical, mental health and psychiatric applications. Conclusion: …. The endless obstructions have resulted in an almost complete halt in research on Schedule I drugs. This is a shame. The U.S. government should move these drugs to the less strict Schedule II classification. Such a move would not lead to decriminalization of these potentially dangerous drugs—Schedule II also includes cocaine, opium and methamphetamine, after all—but it would make it much easier for clinical researchers to study their effects. If some of the obstacles to research can be overcome, it may be possible to finally detach research on psychoactive chemicals from the hyperbolic rhetoric that is a legacy of the war on drugs. Only then will it be possible to judge whether LSD, ecstasy, marijuana and other highly regulated compounds—subjected to the gauntlet of clinical testing for safety and efficacy—can actually yield effective new treatments for devastating psychiatric illnesses.