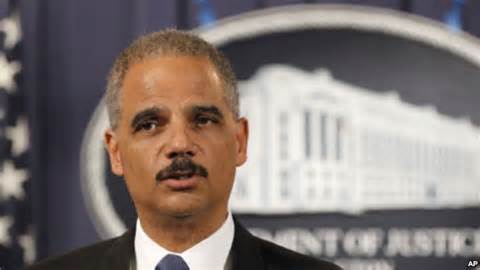

In a speech before the American Bar Association on Aug. 12, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder revealed a plan for reform of the federal court system that could dramatically affect the way that drug crimes are prosecuted. Looking to rein in mandatory sentencing guidelines, which have frequently forced judges to impose steep prison terms on non-violent drug offenders, Holder’s new mandates will require federal courts to reduce the sentences for many of these individuals as long as they do not have ties to organized drug gangs or cartels. Still others will not be sent to jail at all, but will instead be diverted to drug treatment and/or community service programs. Finally, early release will be granted to elderly non-violent drug law offenders who are believed to present no threat to society. The ostensible justification for this change is to reduce prison overcrowding. Federal lock-ups are running about 40 percent over capacity, and about half of those who are incarcerated in federal facilities are there for drug crimes. During the 1980s, when defiant “war on drugs” rhetoric was at its most shrill and strident, Congress, along with the majority of the country’s state legislatures, passed laws requiring people convicted of drug possession to spend a certain amount of time in jail. In general, harsh sentences were mandated even in cases where there was no violence involved in the crimes and regardless of whether the accused were actually selling drugs or just using them recreationally. Naturally this “one size fits all” approach to prosecuting drug crimes has caused prison populations to swell significantly at the state, local and federal levels, much to the chagrin of taxpayers who are expected to fund the entire criminal justice system from top to bottom regardless of how many Americans are put behind bars. Incarceration Rates Skyrocket Because of these laws, the penalties handed out to non-violent drug users over the last three decades have often been every bit as draconian as the prison terms given to hard-core drug dealers. Such an approach is utterly illogical, but it has always been easy for grandstanding politicians to play the demagogue on the drug issue when trying to look tough on crime—much to the detriment of sensible policymaking. Primarily as a result of mandatory sentencing for drug crimes the U.S., the prison population has grown from less than 1 million three decades ago to almost 2.5 million today—even, incredibly, as overall crime rates have declined by more than 20 percent during that same period. As governments at every level have fallen deeper and deeper into debt, the search for ways to cut down on expenditures has gotten increasingly frenetic. This has given greater traction to arguments in favor of drug law reform, made by those who decry the enormous economic and social costs the nation has accrued because of its stubborn determination to criminalize behavior that is frequently related to an illness—specifically, the brain disease of drug addiction. Many have gone so far as to argue that the best course of action would be drug legalization, first of marijuana and then perhaps later of other drugs, since there seems to be little evidence that drug prohibition has reduced consumption or made it more difficult to obtain access to illegal intoxicants. If drugs were to be legalized, taxed, and regulated, far fewer people would be arrested, prosecuted and incarcerated and money would be freed up to fund treatment programs for substance abusers. Treatment or Punishment? Society Must Decide Even if we choose to keep drugs illegal, however, it should still be possible to shrink the prison population significantly by treating drug addiction as a public health problem rather than leaving it to the criminal justice system to manage it through punishment. The shift in policy announced by the attorney general represents an important step in this direction, and it comes on the heels of new initiatives in several states that are designed to reduce prison populations by emptying them of a good portion of their non-violent drug law offending residents. While these reversals in drug prosecution policy are heartening and long overdue, it is notable that the desire to reduce prison overcrowding rather than humanitarian concern is providing the justification for these changes. This is highly unfortunate, because while not all drug users are addicts those who are suffer from a disease and are not going to be “scared straight” simply by being thrown into prison. From a public policy perspective, incarceration is a poor substitute for drug rehabilitation and treatment, and we can only hope that as time passes, the ideology that motivated the push for greater punishment will be replaced by a compassionate desire to get addicts the help they truly need.